Against conscience / for utility

Published by Skeptikos on Jul 21, 2014

Bryan Caplan argues that even dedicated utilitarians are poor utilitarians, and this supposedly shows that, on some level, they aren’t actually utilitarians – their consciences oppose their utilitarian beliefs.

Not long ago he wrote that consequentialism is inherently authoritarian, and presumably that explains this post. Basically, if Bryan Caplan accepts utilitarianism (a form of consequentialism), he’ll be under more pressure to abandon free market anarchism. So the utilitarianism has to go.

The argument disappoints, though. David Hume established long ago that you can’t derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’. That is, you can’t scientifically determine morality, because morality isn’t about facts. It only exists as an abstract concept in animal brains. Technically, the only correct morality is nihilism. There is no objective morality.

But that’s fine because, in every day usage, morality isn’t supposed to describe the world. It’s a matter of practicality and taste, or self-image. People use morality to signal that they care about others, that they’re trustworthy, that they’re Christians, and so on. Therefore when arbitrating between different moralities, we make choices based on taste and judgment. No other standard exists.

Caplan bases his argument against utilitarianism on conscience. Utilitarians don’t live up to the strict standards of their morality, and this shows that utilitarianism conflicts with their consciences. Caplan says we should side with conscience over utilitarianism.

But should we really? Conscience, as an aspect of our brains, evolved just like jealousy, anger, anxiety, or irritability did. Natural selection designed it to promote our genes. As such, it doesn’t provide any obvious guidance to our choice of morality. Conscience is what our genes want, but what do we want?

In everyday life, conscience can work pretty well. People get by just fine with all sorts of moralities, and many rely largely on conscience. It was designed to get people through life, and it works

When it comes to public policy, on the other hand, utilitarianism dominates. And, with a bit of thought, we can see why.

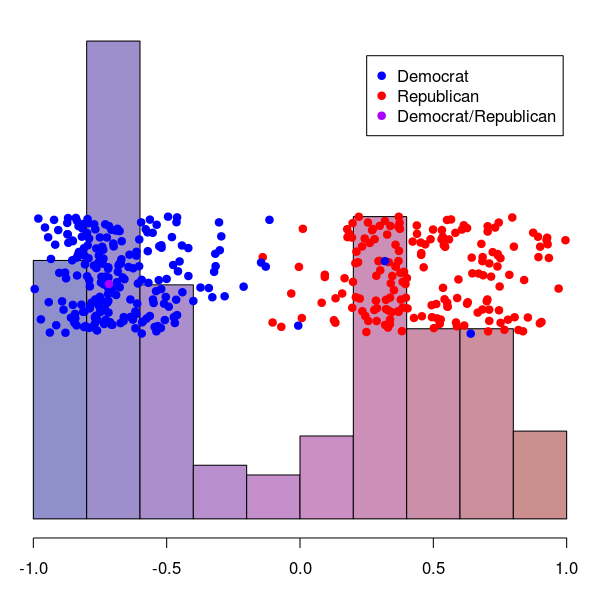

With 300 million citizens, at least in America, we have 300 million different consciences. What if consciences conflict? One person is offended by insurance companies denying sick people benefits; another person running an insurance company would be offended by new regulations. How do we decide which to follow? If there’s no overwhelming majority of consciences, conscience has no clear application to public policy.

We need something more abstract. Utilitarianism basically creates itself here. What fairer way could there be to arbitrate among different people’s preferences than to give equal weight to each person’s happiness, and to prefer the policy with the most happiness? That fits comfortably with most people’s sense of fairness, most of the time. And by definition, any deviation from utilitarianism would leave the world with lower total happiness. That’s hard to justify.

A minority – some egoists, nihilists, and religious people – will totally disagree with this standard, but they don’t get very far. Since we’re talking about public policy, if your philosophy doesn’t convince other people, then it fails. “We should have such and such policy because it serves my self-interest” and “because my religion says so” won’t convince anyone. That’s reason #2 for utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism remains popular because it is a simple, convenient standard for evaluating public policy that fits most people’s sense of morality most of the time. If utilitarianism is inherently authoritarian (i.e., not anarchist), that’s because authority is the practical, moral choice.