How libertarians go wrong

Published by Skeptikos on Aug 1, 2014

There’s a recurring theme in libertarian writing, that liberals mistakenly support left-wing policies because they haven’t bothered to think things through. More often, though, it’s the libertarians who get confused.

Look at Cathy Reisenwitz’s recent article “Kristen Bell is the Latest Celebrity to Fail at Politics and Economics” for an example. She argues that minimum wage supporters don’t understand economics.

Ironically, Cathy herself commits a stream of errors. She writes:

“Raising the minimum wage only works to alleviate poverty if two things are true. First, it must be true that low wages, and not unemployment, is the biggest factor in poverty. Second, it must be true that raising the minimum wage does not, in fact, lead to decreased employment.”

Which just isn’t true. The actual requirement for the minimum wage to alleviate poverty is stupidly simple: it has to end more poverty than it creates.

For those who haven’t been reading about this for six years, here's a brief review:

The minimum wage influences poverty through two main channels: it 1) decreases poverty by providing some poor workers with higher wages, and 2) increases poverty by making it harder for some poor people to find jobs, because employers don’t want to pay the higher wages.

In order to evaluate the minimum wage’s effect on poverty, we need to know the relative impact of these two effects. Thankfully economists have worked tirelessly to find this information.

On 1), economists find that increasing the minimum wage not only increases the wages of those making the minimum, but also, to a lesser extent, increases the wages of those immediately above the minimum. The CBO, a government organization that employs about 200 economists to analyze public policy questions, estimates about 24 million workers would be affected by an increase of the minimum wage to $10.10 (16 million who currently make less than $10.10, and 8 million who make slightly more). That’s 15% of the U.S. workforce.

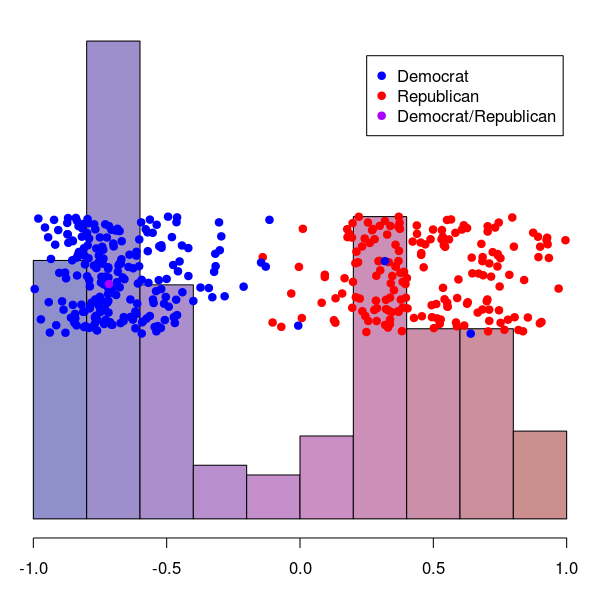

On 2), economists find that increasing the minimum wage has basically no effect on employment at the minimum wage’s current level. Researchers have established this result with a high degree of certainty in the last five years. This graph, based on data from a well-known meta-study, summarizes the current state of the research:

Each point represents one study. The x-axis shows the estimated reaction of employment to a change in the minimum wage. (-5 means, for every percentage point increase in the minimum wage, employment decreases by 5 percent). The y-axis measures statistical accuracy. Higher is more accurate. (As Se, the standard error, decreases, 1/Se increases.)

The pattern on this graph, with more accurate studies consistently finding almost no effect at all, strongly suggests that the minimum wage really does have almost no effect on employment.

The research on questions 1) and 2) lead to the conclusion that increases in the minimum wage decrease poverty, at least around the normal range of the minimum wage. And, as you would expect, the CBO predicts that an increase of the minimum wage to $10.10 would lead to 900,000 fewer people below the poverty line. Due to these findings, many economists, contrary to libertarians, support increasing the minimum wage.

A minority of economists— William Wascher and David Neumark are probably the best known— still oppose the minimum wage, for various reasons. But they’ve become the embattled minority as the evidence mounts against them.

Cathy makes another argument, that big businesses support the minimum wage because it’ll put their smaller competitors out of business. Is this one true?

I did a bit of digging, and, it turns out, smaller retailers do employ more low-wage workers. Some large retailers may support the minimum wage because of that. But Wal-Mart and McDonald’s, at least, have a more compelling reason: a higher minimum wage would put more money into the hands of their customers.

Wal-Mart Chief Says Customers Need Increase in Minimum Wage

Wal-Mart Stores Inc. chief executive H. Lee Scott Jr. called on Congress to raise the country's minimum wage from $5.15 an hour, saying the company's customers are "struggling to get by." ...

"We have seen an increase in spending on the 1st and 15th of each month and less spending at the end of the month, letting us know that our customers simply don't have the money to buy basic necessities between paychecks," Scott said in his speech, a transcript of which was released yesterday.

Would a higher minimum wage help McDonalds — or hurt?

CEO Don Thompson has blamed slowing U.S. sales partly on the waning purchasing power of the company's low-wage “core customers.” ...

“Broadly speaking, certainly getting more money to low-wage families would generate more sales for McDonald's,” says David Cooper, an economic analyst at the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank in Washington.

But Mr. Cooper acknowledges sales likely wouldn't rise much if McDonald's several hundred thousand workers in the U.S. were the only ones who got raises. McDonald's needs a widespread increase in purchasing power among low-wage workers.

Fighting smaller competitors could play a role, but, mostly, companies with many low-income customers seem to honestly believe that an increase in the minimum wage will make their customers better off. (As Cathy would say, “Muh narrative!”)

Cathy makes a half-dozen other arguments, some of them similarly confused. But dealing with them here would distract from the point of the post, which is, how did a libertarian as smart as Cathy write an article so wrong?

I’m not trying to attack Cathy, who does fantastic work challenging libertarian orthodoxy on other issues. Instead, I’m interested in a pattern I’ve noticed among libertarians. Despite believing themselves to be more rational and better informed than non-libertarians, they neglect to do proper research and make basic factual errors. They seem to think that they can uncritically repeat old libertarian arguments and automatically be right.

For example, as far as I am aware, the claim about Wal-Mart’s motivations for supporting the minimum wage originated with this 2005 piece by Lew Rockwell, which is based entirely on speculation. In nine years, did no one bother to double-check to see if there were other explanations?

As for the unemployment arguments, those are artifacts of the ’70s and ’80s, when economic researchers actually did believe that the minimum wage caused significant unemployment. (A variety of factors, including a bias toward publishing only the higher estimates of unemployment, led to the mistaken beliefs.) The last couple of decades have seen a massive reversal of this finding, but the old arguments persist.

Libertarians pass mistaken arguments like these around year after year, apparently without any kind of check to make sure they make sense. It’s as if the brain of libertarianism has been removed, but the body keeps shuffling on.

Why is this happening? Sociology offers a hint. Sociologists consistently find that, when a group of people who agree with each other on some subject are put together, the group becomes more extreme on that issue.

Researchers point to biased information as one of the culprits behind this effect. When joining the group, all of the group members will have reasons for supporting their opinion on the subject. But not all of them will have the same reasons. When the group gets together and exchanges opinions, therefore, some members will hear new reasons to support their positions. They don’t hear new reasons to oppose their opinion, because group members tend not to pass those along. After the group gets together, then, each member has more arguments for their position, and the group as a whole becomes more extreme.

Arguments are passed along in these group situations, not because they are right, but because they support the pre-established group opinion. With the biased information they possess, individuals can’t objectively evaluate their beliefs. This sets the stage for huge factual blunders.

Why don’t libertarians like Cathy account for this bias? One possibility is that libertarians just haven’t thought about it. But the libertarian community tends to be tight-knit (for example, see this post on Free Keene), and it should be obvious that they’re receiving biased flows of information.

More likely, libertarians are just convinced that they’re right. They’ve made big assumptions about the underlying distribution of data (it’s all libertarian!), and thus they don’t think they need to be concerned about the bias. In fact, it’s the rest of the world that’s biased, for some reason or other.

But if that’s the case, then why are libertarians the ones making mistakes?